The Backbone of Industrial Automation: PLCs, HMIs, SCADA & DCS

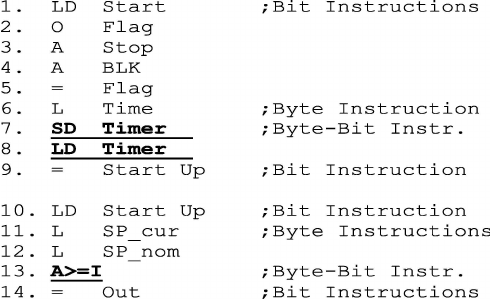

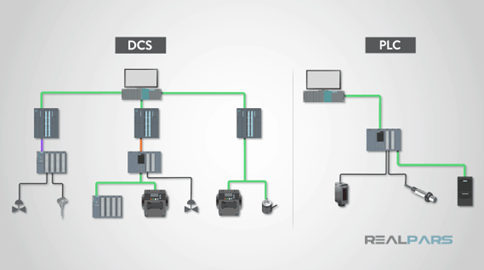

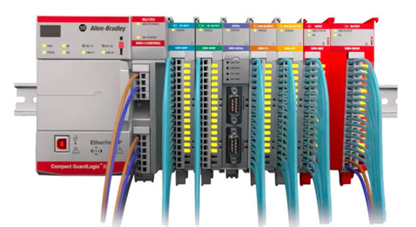

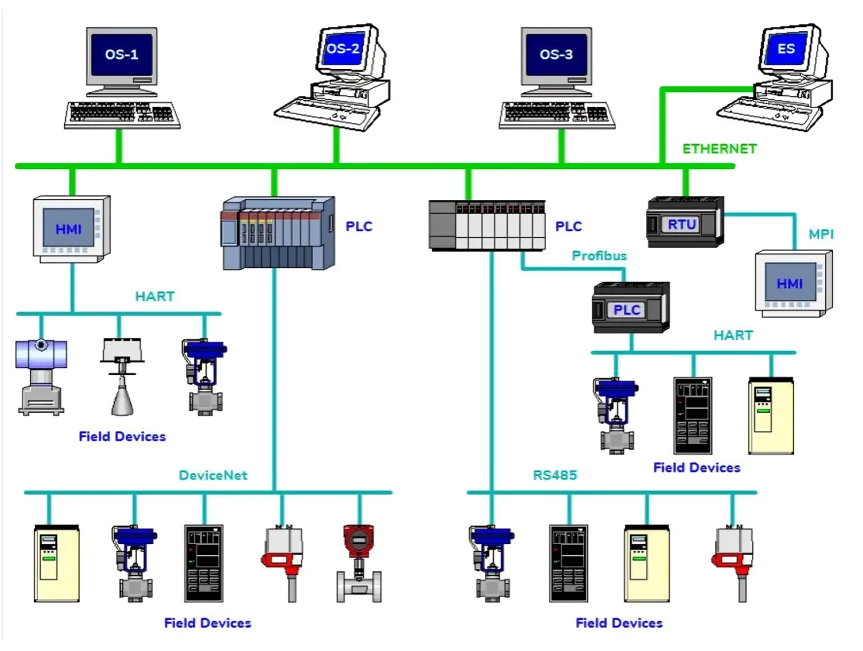

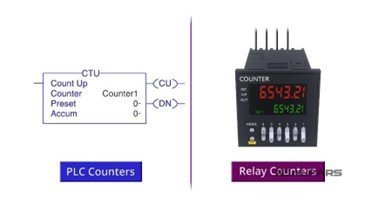

The Backbone of Industrial Automation PLCs, HMIs, SCADA & DCS In today’s fast-paced manufacturing world, automation isn’t a luxury; it’s the standard. At the core of every smart factory and production line, you’ll find one common denominator: Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs). Whether you’re an aspiring automation engineer or a seasoned professional looking to upgrade your skills, understanding how PLCs, Human Machine Interfaces (HMIs), SCADA, and DCS systems work together is essential. Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs): A PLC is a rugged digital computer designed for the harsh conditions of industrial environments. Used to control machinery, monitor inputs and outputs, and automate complex sequences, Programmable Logic Controllers are the brains behind most industrial processes. From packaging lines and bottling plants to chemical reactors and HVAC systems, PLCs are everywhere. Their ability to execute ladder logic, process real-time data, and run continuously without fail makes them indispensable. Popular models include: • Siemens PLC – Known for reliability and global industry standard. • Fatek PLC – A cost-effective and compact solution, popular in Asia. • Mitsubishi PLC – Widely used in high-speed and precise motion control. • Delta PLC – Offers flexible and affordable automation options for small to mid-sized operations. Each PLC brand has its strengths, and selecting the right one depends on your application, scalability needs, and integration ecosystem. HMI: Bridging Humans and Machines: The Human Machine Interface (HMI) is where operators interact with the automated system. Think of it as the dashboard of your car, only for your entire factory. An HMI displays real-time process data, alarms, and control buttons that let technicians tweak the system on the fly. A popular and affordable HMI brand, especially in small and mid-sized industries, is Weintek HMI. These touch-based panels are intuitive, durable, and easily integrate with most major PLCs, including Siemens, Delta, and Fatek. Without HMIs, the world of industrial automation would be a black box, with no feedback, no status, and no real control. HMIs make the invisible visible. The Role of SCADA – Your System’s Nervous System: While PLCs act as the brain and HMIs as the face, the Secondary Control and Data Acquisition System, more commonly referred to as SCADA, serves as the nervous system. SCADA enables centralized control and monitoring across multiple devices, lines, or even geographical sites. Here’s what SCADA systems do: • Collect real-time data from multiple PLCs • Generate trends and reports • Send alerts and alarms • Allow remote supervision and control For instance, in a water treatment facility, SCADA may gather data from hundreds of pumps and valves controlled by Siemens PLCs and display system-wide health on a Weintek HMI. That’s the power of SCADA—macro-level visibility with micro-level control. Distributed Control System (DCS) – Managing Complex Processes: When it comes to process-heavy industries like oil & gas, power plants, and pharmaceutical manufacturing, Distributive Control Systems (DCS) shine. A DCS is similar to a SCADA system but better suited for continuous, complex processes. While PLCs are great for discrete manufacturing (like packaging), DCS handles continuous operations with thousands of process variables. Some key differences: • DCS has integrated control and data acquisition, whereas SCADA often uses separate systems. • DCS is more process-oriented, while SCADA is more monitoring and supervisory-oriented. Both are critical, and sometimes, they’re even used together depending on the plant architecture. Learn the Skills: PLC Courses & Boot Camps: The demand for skilled automation professionals has skyrocketed. That’s where a PLC Course or a PLC Boot Camp can make all the difference. https://iiengineers.com and https://energieintelligent.com Why Take a PLC Course? • Learn ladder logic, function blocks, and structured text • Understand wiring, I/O addressing, and troubleshooting • Practice real-world programming with Siemens, Delta, Fatek, and Mitsubishi PLCs What to Expect in a PLC Boot Camp? These are intensive, hands-on sessions perfect for those who want to jump-start their automation careers. You’ll work with real PLCs, HMIs (including Weintek HMI), and simulate SCADA environments. From configuring a Delta PLC to designing a Weintek HMI layout, a good Boot Camp (iiengineers.com) covers every inch of the automation pyramid. How These Systems Work Together: Imagine this real-world scenario: • A Siemens PLC monitors the temperature of an industrial oven. • A Weintek HMI displays the temperature, oven status, and lets operators adjust the setpoint. • A SCADA system logs the oven data, sends alerts if overheating occurs, and stores reports for regulatory compliance. • In a large facility, a DCS coordinates this oven with 10 others, syncing their operations for optimal energy usage. This is the power of automation when all components—PLCs, HMIs, SCADA, and DCS—work in harmony. Choosing the Right PLC and HMI for Your Project: Here’s a quick comparison table of popular PLCs and HMIs: Brand Strengths Siemens PLC Scalable, widely supported, best for complex systems Fatek PLC Budget-friendly, compact, great for small-scale automation Mitsubishi PLC Fast, motion control capable, robust hardware Delta PLC Flexible, cost-effective, easy integration Weintek HMI Easy to use, highly compatible, intuitive UI Choosing the right components often depends on your project’s needs, communication protocols (Modbus, Ethernet/IP, Profibus), and budget constraints. Final Thoughts: The Future is Automated: The synergy between Programmable Logic Controllers, Human Machine Interfaces, SCADA, and DCS systems continues to evolve, transforming factories into smart, connected ecosystems. Whether you’re building your skills through a PLC Course or exploring advanced configurations of Siemens PLCs and Weintek HMIs, one thing is clear: Automation is the future and it’s already here. So, whether you’re just starting or looking to upgrade your factory floor, now’s the time to dive in. Start with a PLC Boot Camp (iiengineers.com), experiment with Fatek, Mitsubishi, or Delta PLCs, and master the art of integration with SCADA and HMI systems. Want to dive deeper into PLC programming or build your automation setup? Stay tuned for tutorials, guides, and recommended PLC kits for beginners and pros alike. https://iiengineers.com and https://energieintelligent.com